Unreliable Incomes: the fortunes of Waltham Sugar Estate

We are excited to share with you some of the results of the Caribbean Connections project investigating Paxton House’s connections with colonialism and slavery. In this blog post, Dr Charles Fletcher looks the Home Family Archive* to reveal the finances of the Home family’s plantation of Waltham in Grenada following the uprising there in 1795.

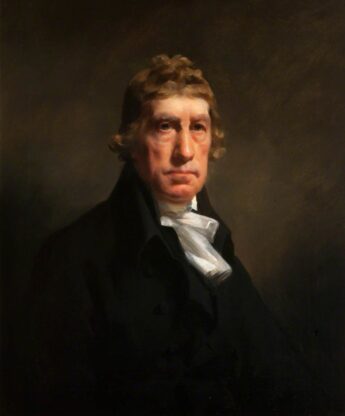

Waltham, a 400-acre plantation on the north-west coast of Grenada, was purchased by Ninian Home in 1764 following the British take-over of the island under the treaty of Paris. The plantation was purchased with the aid of a loan of 187,000 guilders (£17,000) from Rotterdam based lenders Messrs Osy and Son, along with a loan from London-based merchants Messrs Simond and Hankey.[1] Waltham was largely cultivated for sugar which was shipped primarily to London, but also Glasgow, and Bristol as markets demanded and the availability of shipping allowed. Life at Waltham was managed by a white plantation manager and at least two white overseers. Labour was undertaken by enslaved African people, the number of whom fluctuated but stayed in the region of 200 during Ninian Home’s ownership of the plantation.[2] In a good season between 150 to 200 hogshead barrels of sugar would be exported from the plantation.[3] The terms of the loan obtained by Ninian stipulated that all sugar had to be consigned to Simond and Hankey, with the profits being used firstly to pay for the running and upkeep of the plantation. Thereafter the profits were used to service the interest on the mortgage, with an allowance of £1000 permitted to Ninian Home. These were good times for West Indian planters with prices for sugar peaking during the boom years of the early 1780s, during this time Waltham’s profits reached £4000 per year.[4] Ninian managed to ship sugar in 1780/81 during the period the French re-gained control of Grenada (1779-83).[5]

These good times came under increasing threat in the early 1790s. Political instability threatened to upturn the comfortable mercantile world inhabited by white plantation owners, such as Ninian Home. The French revolution and revolt in St Domingo (modern day Haiti) upset the power dynamic in the Caribbean, meanwhile, increasing tensions between the Protestant-British ruling class in Grenada and the Catholic-French planters, who found their rights increasingly threatened by Ninian Home’s policies as Lieutenant Governor, were the root cause of unsustainable tensions on the island. These tensions erupted into violence on 2 March 1795, when Julien Fédon, the son of an enslaved woman and a French planter, rebelled against British rule in Grenada. The freedom fighters were composed of a loose alliance of French (who wished to restore French rule in Grenada), free people of African descent, and enslaved people. Shortly after the uprising began, Ninian was captured and taken hostage near Gouyave, when trying to make his way back to the capital, St George’s. He was among 44 hostages executed by the freedom fighters on 8 April.[6] Reports of the death of Ninian reached Scotland in June.

George Home of Branxton inherited the plantation at Waltham, along with the estate and house of Paxton, following his brother Ninian’s death. George’s inheritance would prove to be a poisoned chalice. The uprising had reduced Waltham to ruins: 45 enslaved people had been killed, the buildings, works, and crops had been destroyed, whilst large expense had been incurred housing and feeding the estate’s free and enslaved workforce during the enforced closure of the plantation. The estate’s losses were estimated at £40,000.[7] Meanwhile, less than half of the huge loans used to purchase the estate thirty years earlier had been repaid.[8] George was also left with the problem of Ninian’s personal debts which, including the sum owed to Osy and Son, stood at around £38,000.[9] George was faced with a dilemma: whether to hand the plantation over to Ninian’s creditors or to undertake a hugely expensive programme of rebuilding. After consulting with several of his deceased brother’s friends in Grenada, including Benjamin Webster and Mather Byles and encouraged by their optimistic estimates of the likely costs of re-establishing the estate, George Home decided to press ahead with the rebuilding programme. He approached Simond and Hankey with a view to borrowing more money. In a letter to his cousin, Patrick Home of Wedderburn, in 1797, informing his cousin that he had been successful in obtaining a loan to finance the re-construction, George confessed to his ongoing regrets concerning Waltham:

“I am disposed to wish that I had been obliged to abandon it [Waltham], and abandon everything else, return to town [Edinburgh] and think of nothing but the light duties of my office… the idea is wise because it is selfish.’”[10]

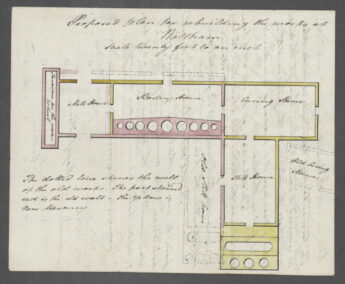

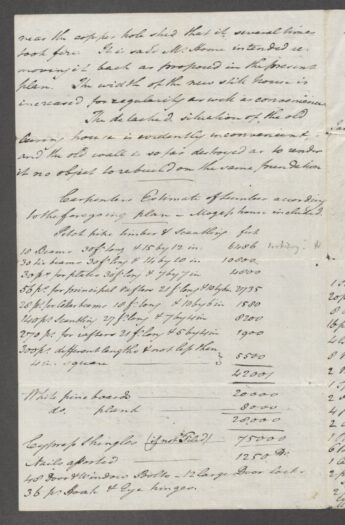

George claimed that his resolve to rebuild stemmed not from concerns for his own finances, but rather from his paternalistic outlook for those connected with the estate, who were dependent upon him for their livelihoods. George Home also expressed concern for the care of the enslaved people at Waltham and this was another motivation for continuing with the estate. In a letter to estate the estate doctor, Thomas Duncan, he wrote that “care and attention to their [the enslaved people’s] health and comfort which is much more pleasing to me than every increase of produce”.[11] The eventual re-establishment of the estate cost more than twice the initial estimates, with total costs running to £16,000. Of this sum, £7,319 was lent by Simond and Hankey, a further £6000 came from the British government, with George Home footing the remaining £2558.2.9.[12] The most urgent task in the rebuilding project was to put the enslaved people’s allotments back under cultivation. Providing a reliable and cheap source of food for the enslaved workforce was crucial to both the rebuilding programme and the running of the estate. Of the buildings at Waltham, the boiling house, still house, curing house, water wheel, hospital, manager’s dwelling house, and 30 enslaved people’s houses all required some form of re-construction. 120 cows and 25 mules had been killed or carried off and these had to be replaced, with some of them being shipped from Britain. For instance, in September 1798, six mules, two mares, and a jack ass were shipped to Waltham.[13] It took six years for the plantation to resume full production, by that time Waltham’s debt stood in the region of £30,000.[14]

The challenges of rebuilding coincided with difficult economic times for the West Indian planters, with war and depressed markets dramatically reducing profits. George Home had astutely appointed Berwickshire man John Fairbairn, formerly employed at Wedderburn, to take over the management of Waltham. Under Fairbairn’s management a programme of ‘economy’ was implemented which saw day-to-day running costs cut in all quarters. Fairbairn’s austerity measures took many forms, from sharing paper with others writing home to Scotland to save postage, to forcing the enslaved people to subsist almost entirely off the allotments provided for them, meaning that much reduced stores of food could be sent from Britain. Fairbairn admitted that he was shocked to see so much food being imported from Britain to feed the enslaved people;

“…at first when I took charge of the estate I had great trouble with it for the ship stuff and flour was as I thought only wasted upon them [the enslaved people] and what was worse some of them depended upon being feed from the hand.”[15]

Under Fairbairn’s management the income realised from Waltham averaged £2000 yearly.[16] The immediate concern was to pay back the public loan which was quickly achieved; however, George Home continued to entertain thoughts of abandoning the estate to its creditors and thus freeing himself of all his West Indian obligations. In a letter dated 1805 to James Campbell, a planter and owner of enslaved people in Tobago, Grenada and St Vincent, George Home revealed his anxiety over Waltham’s mounting debts:

“…you will readily believe that my most earnest wish is to get free of debt, and to pass the remainder of my days free from the anxiety of storms and seasons and the merciless demands of London Merchants – This I am afraid I cannot accomplish in any other way than by the sale of Waltham.”[17]

Slow but steady progress continued to be made in reducing the estate’s debts, yet five years later, sale was still on George’s mind when he asked the Grenada based lawyer, Richard Landreth, to undertake a valuation of Waltham. To George’s horror, Landreth valued the estate at less than the original purchase price. In fact, the only assets on the estate which were appreciating in value were the enslaved people who had increased in value due to the cessation of the slave trade.[18]

Indeed, such were the financial pressures entailed in running Waltham that George Home’s previously healthy personal finances had been placed in jeopardy. In a letter to his London merchant, Thomson Hankey, George Home lamented that; ‘I never knew what the want of money was till I had a concern in the West Indies’.[19] He was forced to divert income from his Scottish estates and his pension as a principal clerk to the court of session (in Edinburgh), to sustain Waltham and drew no income from the plantation at all.[20] Nevertheless, perseverance and improving markets meant that, twenty years following George Home’s succession, the loans advanced to re-establish Waltham were finally repaid; however, the original, and still outstanding, loans contracted by Ninian still cast a shadow.

The European wars had afforded George Home some breathing space in the repayment of the loan from the Rotterdam lenders Osy and Son. Since 1795, this had ballooned beyond its original size, due to the non-payment of interest. In 1814 negotiations began over a new repayment settlement. Under the agreement, reached through the mediation of Thomson Hankey, the first £1500 net profit from each year’s sugar crop was to be applied to repaying the interest and principal sum owed to Osy and Son [this debt was finally repaid in full in 1836].[21] 80% of the remainder was to be used to pay off the original debt still owed to the Merchants Simond and Hankey. The remainder was remitted to George Home who, for the first time, was permitted to draw an income from the plantation.[22] In 1815, out of the £4,517 net profit realised, George Home was paid £500.[23] He received the same in 1816, slightly less in 1817; the largest sum he received was £588 in 1818.[24] Low sugar prices in 1819 meant that George Home appears to have drawn no money from Waltham that year, choosing instead to apply all of the profit to repaying Osy and John Hankey’s executors.[25]

Thanks to the large debts he had inherited, during his lifetime George Home derived only a relatively small amount of money from his plantation and the work of the enslaved people who laboured upon it. Waltham was profitable enough to eventually pay off its debts; however, the records indicate that it did not directly finance any of the improvement schemes for the house and grounds, such as the Library and Gallery, at Paxton in the early years of the nineteenth century. Following George Home’s death in 1820, the output from Waltham declined drastically and profits fell in line with the reduced output. After nearly 70 years, the loan from Osy and Son was finally discharged in 1835.[26] The estate of Waltham was sold in 1844 for only £2500.[27]

*The Home family archive is in the care of National Records Scotland, ref. GD267. Intro image, View of Waltham Plantation, 1969 by John Benjamin, copyright The Paxton Trust.

With funding from The Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund delivered by the Museums Association, as part of the ‘Parallel Lives, World’s Apart’ project, the slavery-related archives of the Home family that owned Paxton House, are being made available online via Paxton’s collections database ‘Ehive’ @ https://paxtonhouse.co.uk/discover/history/collections/

Dr Charles Fletcher has checked, summarised, and uploaded nearly 700 documents from the Paxton archive. This blog discusses one aspect of the history which is also explored in the permanent exhibition within Paxton House; ‘Caribbean Connections, Paxton, and Slavery’ and in the costume exhibition ‘Parallel Lives, Worlds Apart’.

@EsmeeFairbairn @PaxtonHouse @descendants93 @MuseumsGalScot @Textile_Society @MuseumsAssoc @SirGeoffPalmer

[1] Messrs Osy & fils, Rotterdam to Ninian Home concerning the Waltham loan. 25 Febr… on eHive

[2] Treatment of enslaved people – Paxton House

[3] A hogshead varied in size and might be anywhere between 360 and 680 kg in weight.

[4] Statement of Ninian Home’s debts as they stood in autumn 1792 total £38 100.; N… on eHive

[5] GD267/1/3/36 and GD267/1/3/37.

[6] Around 7000 enslaved people are believed to have been killed during the uprising, not only in battle, but also of disease, starvation, and in reprisals by British forces.

[7] Estimate of the losses sustained at Waltham due to the insurrection, including a… on eHive

[8] Waltham Mortgage account with Osy and Sons 1794 – 1833; 1833; GD267/5/51/11 on eHive

[9] Statement of Ninian Home’s debts as they stood in autumn 1792 total £38 100.; N… on eHive

[10] Letter – George Home to Patrick Home 19 April 1797 Conforms that a loan of £600… on eHive

[11] Letter – George Home to Dr Thomas Duncan 6 October 1811 State of the enslaved p… on eHive

[12] Letter – George Home to Richard Landreth 27 Dec 1810 Details of the debts on th… on eHive

[13] Simond and Hankey’s account 30 June 1798-30 June 1799 Stores shipped to Waltham… on eHive

[14] Letter Book – George Home to Mather Byles 8 September 1801 George admits that … on eHive

[15] Letter – John Fairbairn to George Home 9 July 1813 Shipping/prices – complaint … on eHive

[16] The biggest profit realised was in 1816, when £6333 net was earned from Waltham sugars. Letter Book – George Home to John Fairbairn 13 July 1816 Gross profit from 190 … on eHive

[17] Letter Book – George Home to James Campbell, Tobago, 2 November 1805 Thanks him… on eHive

[18] Letter – Richard Landreth (Grenada) to George Home 1 April 1810 Landreth’s valu… on eHive

[19] Letter – George Home to Thomas Hankey 19 June 1809 Thanks him for taking care t… on eHive

[20] Letter Book – George Home to James Campbell, Tobago, 15 February 1805. Hopes h… on eHive

[21] It is likely that part of the compensation money was used to secure the release from the mortgage; however, in a letter from John Foreman Home to Thomson Hankey written in early 1835, John Foreman Home stated that his solicitor had already been furnished with the necessary funds to repay the outstanding sums due under the terms of the mortgage ‘immediately’, this was over 10 months before the compensation money was received.

[22] Letter book – George Home to Thomson Hankey 16 March 1814 New mortgage repaymen… on eHive

[23] Letter Thomson Hankey to George Home 11 May 1816 Accounts of sale of crops from… on eHive

[24] Brief account of sugar sold annually from Waltham 1810 -1817, number of barrels,… on eHive

[25] Thomson Hankey to George Home 30 April 1819 Waltham’s account after sale of the… on eHive

[26] Documents relating to the release of Messrs Osy’s mortgage on Waltham from Mr Wi… on eHive

[27] Letter – Thomas Duncan to William Foreman Home 23 May 1844 Has sold Waltham to … on eHive