Treatment of enslaved people

Dr Charles Fletcher has been looking for evidence in the archives for the treatment of the enslaved people working on the Home family of Paxton’s Grenadian estate of Waltham.

It is difficult for us to understand the nature of life at Waltham for the enslaved people forced to work there; however, the records within the Home family archives give us some idea of the conditions that they endured during their enslavement.

The estate of Waltham on the north-eastern coast of Grenada was purchased by Ninian Home in 1764.[1] It remained in the ownership of the Home family until its sale in 1848. Waltham extended to 400 acres of land which were primarily given over to the production of sugar for the British market. Included in the purchase price were enslaved people, most of whom had arrived on the island whilst it was under French rule, and who were treated as chattels of Ninian Home. The number of enslaved people at Waltham fluctuated over time: in 1788 an inventory of the enslaved people upon the estate tells us that the enslaved population was 203: 105 men, 75 women and 23 children.[2] In 1816, following the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, the enslaved population at Waltham had dropped slightly to 195.[3] This number continued to slowly reduce over the next fifteen years; however, in 1832 the new owner William Foreman Home (who had inherited Waltham from his cousin George Home of Wedderburn in 1820) arranged for 90 enslaved people to be transferred from the neighbouring plantation of L’Est Terre to Waltham as part of a deal to settle his younger brother’s debts with the Marryat family.[4] Because of this transaction, the number of enslaved people at Waltham at the time of the abolition of slavery stood at 247.[5].

Reading through the Home family archives we begin to get a clearer picture of what everyday life was like on Waltham estate. The enslaved people at Waltham were housed in a village of small houses, a model of which can be viewed in the Caribbean Connections Exhibition in Paxton House. These were probably built largely from timber and thatched with waste material available freely on the estate. More ‘important’ buildings on the estate, such as the manager’s house and hospital, were clad and roofed with wooden shingles. In a valuation of Waltham undertaken in 1775 the enslaved-people’s houses were valued at £10 each.[6] However, over time, as little money as possible was spent on the enslaved people’s accommodation; in 1833, Waltham manager John Foreman Home of Wedderburn boasted that ‘all the new houses [for the enslaved people from L’Est Terre] cut a respectable figure and which I have put up without one shilling of expense.’ [7]

Reading through the Home family archives we begin to get a clearer picture of what everyday life was like on Waltham estate. The enslaved people at Waltham were housed in a village of small houses, a model of which can be viewed in the Caribbean Connections Exhibition in Paxton House. These were probably built largely from timber and thatched with waste material available freely on the estate. More ‘important’ buildings on the estate, such as the manager’s house and hospital, were clad and roofed with wooden shingles. In a valuation of Waltham undertaken in 1775 the enslaved-people’s houses were valued at £10 each.[6] However, over time, as little money as possible was spent on the enslaved people’s accommodation; in 1833, Waltham manager John Foreman Home of Wedderburn boasted that ‘all the new houses [for the enslaved people from L’Est Terre] cut a respectable figure and which I have put up without one shilling of expense.’ [7]

The clothing that enslaved people were provided with was extremely limited. Young boys and girls were issued with a simple shift linen dress which would have had to last until it was probably threadbare. Replica 18th century examples of clothing for enslaved people and children are displayed in the Drawing Room and Library at Paxton House. All the clothing allocated to the enslaved people at Waltham was dispatched from Scotland and each enslaved person had an annual allowance.

The clothing that enslaved people were provided with was extremely limited. Young boys and girls were issued with a simple shift linen dress which would have had to last until it was probably threadbare. Replica 18th century examples of clothing for enslaved people and children are displayed in the Drawing Room and Library at Paxton House. All the clothing allocated to the enslaved people at Waltham was dispatched from Scotland and each enslaved person had an annual allowance.

Eighteenth century Scottish weavers had ready market exporting this cloth and clothing to the colonies. Occasionally enslaved people were rewarded for hard work or loyalty through the provision of extra articles of clothing. For instance, the head carpenter, Fido, requested a great coat from George Home in 1814, this too was exported from Scotland and was sent to estate manager John Fairbairn to give to Fido.[8]

To save the estate money and to ensure a supply of fresh and nutritious food, the enslaved people were encouraged to grow as much of their own food as possible at Waltham. They were provided with allotments for this purpose and were given time to tend to their crops; in April 1818, George Home of Wedderburn encouraged his manager at Waltham to assist the enslaved people to put their allotments in order. He wrote that his motivation for doing so was that ‘whatever is advantageous to them is in effect a profit to me’.[9] As a further inducement, the enslaved people were allowed to sell any surplus produce and keep the profit for themselves. Sometimes this policy had unintended consequences; George Home wrote about these to his London agent Thomson Hankey: ‘many of them [the enslaved people] have a great deal to carry to market and they are so fond of money, that lately when provisions were very dear, he [John Fairbairn, estate manager] was obliged to establish a night watch to prevent their carrying all to market and not leave enough to maintain themselves’.[10] In addition to fresh fruit vegetables, and locally caught fish, further dried and preserved food stuffs were exported from Britain to supply the workforce at Waltham. For the enslaved people, the principal imported foodstuffs were salt, and salt fish (from Newfoundland), if the preferred type of salt fish was too expensive then these were substituted with Scottish herrings. Beef hearts and skirts were also imported from Britain. At Christmas time the enslaved people were provided with a special beef ration, an indulgence provided at the insistence of George Home.[11]

Fuelled by this diet, the enslaved people at Waltham were forced to carry out a great array of both menial and laborious tasks upon the plantation. Adult males of working age were generally split between those who undertook menial roles in the fields growing and harvesting the crops, and those who held a position as a skilled tradesman, such as a carpenter, mason, distiller, boiler, or cooper. Women too were expected to undertake hard manual labour working as field hands, or as domestics; however, chillingly, they were prized for their breeding potential above all. This aspect of the plantation economy is made clear in a letter from John Fairbairn to George Home in November 1813. In the letter, Fairbairn laments the death of an enslaved woman named Philis, aged 19, who died following the birth of her second child and despite the care administered by Fairbairn and the estate doctor: ‘the poor young woman I now talk of was about 4 years old when I came to the estate… as she was lickly to be a breeder it makes the loss the more sevear’.[12] Women who had young children, or were prepared to look after other women’s children, were exempted from work, sometimes for up to a year. Rather than being an act of kindness, this was supposed to be an inducement for women to have children and thus, inadvertently increase the workforce upon the estate. By the time these children reached the age of seven, but sometimes even as young as five, they were also expected to work. They began in the grass gang (comprised of children and the elderly), who provided fodder for the livestock on the estate and weeded crops. The children gravitated from this lighter work to being field hands in their early teens.

Fuelled by this diet, the enslaved people at Waltham were forced to carry out a great array of both menial and laborious tasks upon the plantation. Adult males of working age were generally split between those who undertook menial roles in the fields growing and harvesting the crops, and those who held a position as a skilled tradesman, such as a carpenter, mason, distiller, boiler, or cooper. Women too were expected to undertake hard manual labour working as field hands, or as domestics; however, chillingly, they were prized for their breeding potential above all. This aspect of the plantation economy is made clear in a letter from John Fairbairn to George Home in November 1813. In the letter, Fairbairn laments the death of an enslaved woman named Philis, aged 19, who died following the birth of her second child and despite the care administered by Fairbairn and the estate doctor: ‘the poor young woman I now talk of was about 4 years old when I came to the estate… as she was lickly to be a breeder it makes the loss the more sevear’.[12] Women who had young children, or were prepared to look after other women’s children, were exempted from work, sometimes for up to a year. Rather than being an act of kindness, this was supposed to be an inducement for women to have children and thus, inadvertently increase the workforce upon the estate. By the time these children reached the age of seven, but sometimes even as young as five, they were also expected to work. They began in the grass gang (comprised of children and the elderly), who provided fodder for the livestock on the estate and weeded crops. The children gravitated from this lighter work to being field hands in their early teens.

Working conditions on the plantation were dangerous; industrial accidents and disease were common. The long working hours undoubtedly contributed to the danger. These hours were kept as long as they possibly could be without compromising the work rate of the enslaved people. During crop time, night and day shifts were instituted to ensure that the mills and stills could be kept running without pause, until the whole sugar crop was completed. In 1815, John Fairbairn became one of the first plantation managers in Grenada to stop round the clock working, instead introducing a working day which began at 5 a.m. and ceased at midnight. This he found left the enslaved people feeling ‘fresh in the morning’ and had the added bonus of eliminating workplace accidents without a reduction in the amount of sugar produced.[13]

Working conditions on the plantation were dangerous; industrial accidents and disease were common. The long working hours undoubtedly contributed to the danger. These hours were kept as long as they possibly could be without compromising the work rate of the enslaved people. During crop time, night and day shifts were instituted to ensure that the mills and stills could be kept running without pause, until the whole sugar crop was completed. In 1815, John Fairbairn became one of the first plantation managers in Grenada to stop round the clock working, instead introducing a working day which began at 5 a.m. and ceased at midnight. This he found left the enslaved people feeling ‘fresh in the morning’ and had the added bonus of eliminating workplace accidents without a reduction in the amount of sugar produced.[13]

The treatment of the enslaved people at Waltham will shock many modern-day readers, as it did many people at the time; however, it was undoubtedly more humane than on many other Caribbean estates, especially those which were left solely in the hands of overseers who depended upon sustained high output from the plantation for their continued employment. Ninian and George Home clearly believed that the treatment of the enslaved people at Waltham should attain a certain moral standard. Thus, whilst there are examples of abuses being perpetrated at Waltham, such as the abuse meted out by the overseer Ninian Jaffray, the Home family and their managers generally pursued a policy of what was, considered to be, relatively humane treatment of the enslaved in the hope of achieving greater economic output. Health care and inoculations were provided, and physical punishment was largely avoided. The correspondence between Paxton and Waltham often mentions the term ‘humanity’, whilst recommending good treatment of the enslaved people and describing the enslaved people as being the manager’s ‘family’:

“for my part I would not employ the nearest friend I have tho he were the last planter in the West Indies unless I could depend upon his humanity to the people he has under his care, a manager of a plantation should consider himself as the father of the slaves and treat them with tenderness, they are human beings as well as ourselves and very capable of distinguishing between what it right and what is wrong.”[14]

However, these terms will strike the modern-day reader as being somewhat patronising and cynical considering the motivations for the acts of leniency and kindness which were adopted.

With funding from The Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund delivered by the Museums Association, as part of the ‘Parallel Lives, World’s Apart’ project, the slavery-related archives of the Home family that owned Paxton House, are being made available online via Paxton’s collections database ‘Ehive’ @ https://paxtonhouse.co.uk/discover/history/collections/

Dr Charles Fletcher has checked, summarised, and uploaded nearly 700 documents from the Paxton archive. This blog discusses one aspect of the history which is also explored in the permanent exhibition within Paxton House; ‘Caribbean Connections, Paxton, and Slavery’ and in the costume exhibition ‘Parallel Lives, Worlds Apart’.

@EsmeeFairbairn @PaxtonHouse @descendants93 @MuseumsGalScot @Textile_Society @MuseumsAssoc @SirGeoffPalmer

[1] Ninian Home (1732-95) was the second owner of Paxton House (from 1773), and latterly Lieutenant-Governor of Grenada from late 1792 until his execution in Fédon’s Uprising on the island. His younger brother, George Home (1735-1820), inherited both estates.

[2] List of slaves belonging to Ninian Home at Waltham, Grenada, 1 June 1788.; Ninian Home; 1788; GD267/5/17/9x

[3] Letter Book – George Home to John Fairbairn 3 August 1816 Wet weather in Grenada but prospect of good crop. Asks for account of numbers of enslaved people on the estate but ‘I want no list, you sent me a distinct one last year’ when there were 195 enslaved people in all. Worry about declining numbers. No market for rum with so much distillation at home.; George Home; 1816; GD267/5/38 p. 14

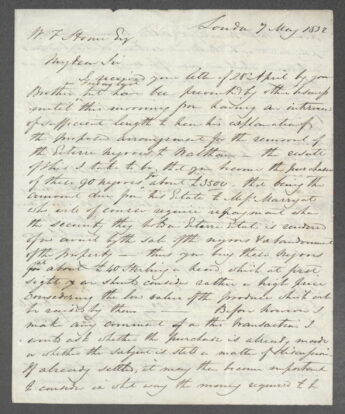

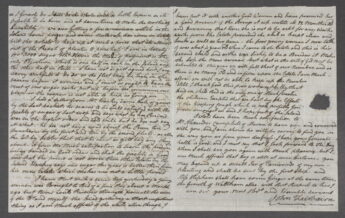

[4] Letter – Thomson Hankey to William Foreman Home 7 May 1832 Regarding the possible purchase of the enslaved people on L’Est Terre, owned by John Foreman, estate for Waltham. The purchase would be of 90 enslaved people for £3500, £3500 being the sum owed by Dr Foreman to Marryat. They will require repayment when the security they hold on L’Est Terre estate is rendered null by the removal of the enslaved people and the abandonment of the estate. ; Thomson Hankey; 1832; GD267/5/3/7

[5] Details of Claim | Legacies of British Slavery (ucl.ac.uk)

[6] An Inventory and Valuation of the Lands, Buildings, Slaves and Stock of Waltham Estate the Property of Ninian Home esquire situated in the Parish of St Marks & Island of Grenada. 1 September 1775; 1775; GD267/5/20/1

[7] Letter – John Foreman Home of Wedderburn (Waltham) to William Foreman Home of Paxton 28 September 1833 News from Waltham describing John Foreman’s first year in charge.; John Foreman; 1833; GD267/5/32 28/09/33

[8] Letter book – George Home to John Fairbairn 15 October 1814 Dr Duncan and family are at Paxton. Glad to hear that work on the house and still goes on well. Disappointed that Hankey has once again failed to judge the sugar market well and sold whilst prices were low. Will send a great coat to Fido [an enslaved person?] it is up to Fairbairn to judge whether or not he deserves it.; George Home; 1814; GD267/5/36 p. 67

[9] Letter Book – George Home to John Fairbairn 11 April 1818 GH expresses anxiety over the situation in Waltham – health of enslaved people, encourages Fairbairn to assist with putting their gardens in order, as ‘whatever is advantageous to them is in effect a profit to me’ – wet and cold weather delaying cultivation in Berwickshire; George Home; 1818; GD267/5/38 p. 59

[10] Letter Book – George Home to Thomas Hankey 14 September 1813 Increase in prices agreeable – 10 barrels of Rum to be sent from Fairbairn, no market for Rum in Grenada is making it difficult to pay the white people’s salaries – Enslaved people’s gardens at Waltham – ; George Home; 1813; GD267/5/36 p. 38

[11] Letter – George Home to John Fairbairn 26 July 1809 Accounts – fish cheaper from Britain rather than buying locally, estate have not been hiring out their tradesmen, Christmas indulgence for the enslaved: ‘I see nothing in this years accounts for a merry making to the Negroes at Christmas, I hope it is an omission and that you have not curtailed them of that little indulgence.’ News of John Foreman who denies remarks regarding Fairbairn.; George Home; 1809; GD267/5/35 p. 27

[12] Letter – John Fairbairn to George Home 16 Nov 1813 Death of Philis one month after child birth. Fairbairn has placed the child with another woman who he has freed from work and promised a gift if she will keep it for 12 months and raise it as well as her own. Fairbairn laments the loss of Philis as being an enslaved person of ‘value’ and worries about diminishing numbers on the plantation. Promises tamarind and ginger for Nancy Stephens.; John Fairbairn; 1813; GD267/5/24/32

[13] Letter – John Fairbairn to George Home 26 June 1815 Sugar crop – expects to complete boiling this evening and will ship the equivalent of 201 hogsheads. This year instead of working around the clock, as is the custom on the other estates, he instead had one shift from 5 am until midnight and found that the enslaved people were better rested and produced the same amount of sugar. Imagines that most other estates will adopt this practice. No accidents to enslaved people or mules. Old custom in the quarter of the island is that the manager who produces the most sugar must feed the other plantation managers and this year that honour falls upon Fairbairn in the parishes of St John’s and St Mark’s. This is only the second time this has happened, the other being 1805. Plans to serve the beef that Miss Stephens sent from Paxton and admits to being ‘a little elated’. Rum; John Fairbairn; 1815; GD267/5/24/55

[14] Letter Book Ninian Home (Paxton House) to Ninian Jaffray (Grenada) 22 October 1789. Discussion of his misconduct as overseer. Recommends kindness and humanity to the slaves.; Ninian Home; 1789; GD267/7/1 22.10.89