Henry Raeburn at Paxton House

John Campbell, 1st Marquess of Breadalbane by Henry Raeburn, on loan to Paxton House from National Galleries Scotland

Sir Henry Raeburn (1756-1823), one of Britain’s most celebrated portrait painters, died unexpectedly in July 1823, just after returning to Edinburgh from an excursion with friends. Two hundred years later, his works are scattered across the globe, in major collections in the USA and in the National Gallery of Scotland, while Paxton House has significant group of his portraits. The collection, hung in the Study and the Picture Gallery, includes works on loan from National Galleries Scotland, and spans the painter’s career, giving an insight into Raeburn’s status as a painter.

Born in Edinburgh in 1756, Henry Raeburn hardly ever left the city of his birth but he stands among the greatest painters of the age. Today his portraits capture for us all the major figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, the period when Scotland was the intellectual powerhouse of Georgian Britain.

The earliest of his portraits in the Picture Gallery at Paxton is a head and shoulders portrait of Robert Montgomery (1774-1854). This early work is a good starting point for understanding how Raeburn’s career developed. Montgomery was a lawyer, who later became Lord Advocate of Scotland, but this portrait has been cut down from a full-length view of Montgomery in hunting clothes. When the portrait was painted, around 1790, Montgomery was in his twenties and newly qualified; Raeburn chooses to show him lit from the left and behind, a technique he had learned on a visit to Rome a few years earlier. The loose technique of this portrait contrasts with the more mature portrait of another lawyer, George Home of Paxton, which hangs in the Study. Painted perhaps fifteen years later, by this time the Edinburgh legal profession had proved a mainstay of Raeburn’s clientele. The sombre colours and focus of light on the face gives the sitter a seriousness which flattered his subjects.

Success came early to Henry Raeburn. He was briefly apprenticed to a goldsmith, and by the mid 1790s he was already established as an artist with a studio in George Street, married to a wealthy widow and father to two sons. His youngest son, Henry, appears in a portrait at Paxton which is probably a copy, by another hand, of a sketch Raeburn made of his son on a grey pony around 1796, perhaps for a full size portrait of The Drummond Children, now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. He was to become an accomplished painter of children. Arguably, the prettiest portrait at Paxton is of Grace, Lady Milne, painted shortly after her marriage around 1804; it has all the romantic grace of Raeburn’s contemporary, Sir Thomas Lawrence, whose work may have been an influence at this time. Grace married Admiral Sir David Milne whom Raeburn painted in a handsome full-length portrait in his naval uniform which today hangs beside her and around which the furniture in the room was arranged. Grace’s early death in 1814 was a terrible blow to her husband, leaving him with two young sons, one of whom would grow up to inherit Paxton House.

Another of Raeburn’s female subjects has a similarly romantic air and may also have been a marriage portrait; Margaret Scott of Logie, painted around 1806. An heiress, she married a solder, John Hope, who rose to become a General in the Duke of Wellington’s Peninsula War against Napoleon. In contrast, another portrait of a woman by Raeburn has a different story to tell, of a mature confident woman, Jean Adam, Mrs Kennedy of Dunure. The portrait is a pair with one of her husband in the National Gallery of Scotland’s own collection; the paintings were made for her son about three years after the couple separated in 1808. Jean’s place here is earned through her father John Adam who, with his brothers James and Robert Adam, were responsible for the architecture and interiors at Paxton House.

Two impressive full length portraits by Sir Henry Raeburn in Paxton’s Picture Gallery belong to his busiest period. In 1808, he filed for bankruptcy after his investment in a trading company failed and he was then forced to take on as many commissions as he could to repay his debts. On the right of the fireplace hangs a portrait of a young man in riding breeches, looking confident and a little self-satisfied in a portrait style adopted by Raeburn for many of his landowning patrons. This is John Wilson of Elleray painted when he was about 22, newly graduated from Oxford, independent and the owner of an estate in Cumbria. He might have been forgotten by history but for misfortune. A bad investment by his uncle left him penniless within a few years of the portrait. He moved to Edinburgh, trained as a lawyer and became co-founder and principal writer for Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, one of the nineteenth century’s most controversial and successful publications. Its success was largely due to Wilson’s contributions which were an opinionated and combative mix of satire, reviews and criticism, under the pseudonym, ‘Christopher North’. He was at the centre of Scottish intellectual life, also holding the Chair of Moral Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh.

On the other side of the fireplace is a later portrait dating from around 1822, shortly before Raeburn’s death. It shows John Campbell, 1st Marquess of Breadalbane, owner of vast estates in Perthshire at heart of which sits fabulous Taymouth Castle, a vast gothic edifice, commissioned by Campbell in the 1850s with little thought for expense. This mature work from Henry Raeburn shows all his skill in capturing character and his typical lighting style which creates drama in the composition.

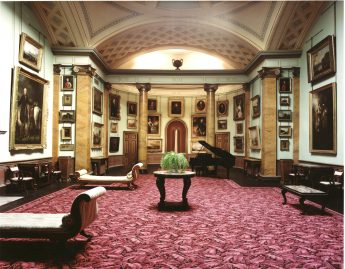

The portraits in the Picture Gallery are looking their best thanks to another connection between Henry Raeburn and Paxton House. When George Home of Paxton commissioned the construction of the Picture Gallery in 1813, originally to house his uncle’s Grand Tour purchases, he turned to his portraitist, Raeburn, for advice on its design. It was Raeburn who advised on the top lighting from the central cupola and two lunettes in the roof; a revolutionary design at the time which was to influence the design of picture galleries through the coming century.

When Henry Raeburn was knighted by George IV as his official royal painter in Scotland in 1822, he had already captured in paint many of the leading men and women of the day. A visit to the collection at Paxton is an ideal introduction to one of Scotland’s foremost painters, tracing both the development of his skill and introducing us to some of the people who mattered in Regency Scotland from peers to intellectuals.

Book here.