Celebrated Abolitionist at Paxton House

Black History Month

Two hundred and fifty years ago, on 20 August 1773, a sixteen-year-old boy was baptised as ‘John Stuart’ in London at St James’s Church, Piccadilly. Why is this important? That boy’s birth name was Quobna Ottobah Cugoano and he became one of the great anti-slavery campaigners of 18th century Britain, calling for total abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire. Paxton House’s curator, Dr Fiona Salvesen Murrell tells his story.

Why is this baptism relevant to Paxton House? As Cugoano himself related, he had been bought by Alexander Campbell (1739-1795)[i] on the

Caribbean Island of Grenada and was brought by Campbell to Britain as his personal servant in 1772. On board the same ship were Campbell’s close friends, Ninian and Penelope Home, owners of Waltham plantation in Grenada. The Home’s shared part-ownership of Paraclete plantation in Grenada with Campbell and remained close friends during their lifetimes. Prior to, during and after this voyage, Cugaono was in very close proximity to the Homes and his master and enslaver. This was Cugoano’s second transatlantic voyage; the first had been from Ghana in West Africa to Grenada, around two years earlier, at the age of thirteen.

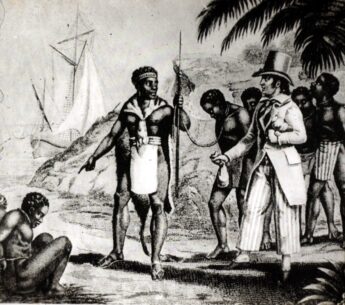

Cugoano had been playing in the forest with friends when they were kidnapped by African men. The children were separated over their journey to the coast and Cugoano was taken and sold at a coastal fort where the terrible reality of what was happening to him was evident with the brutality he witnessed. He was put on board a slave ship and, unlike many others, Cugoano survived the horrific conditions on board. Such was their misery, that the women and children with the agreement of the male enslaved people, who were almost constantly in chains below deck, plotted to set the ship on fire to end all their lives rather than continue. This was foiled and Cugoano was brought ashore in Grenada and worked as a field slave initially. He was one of around 12.5 million Africans trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean, of whom around two million died en-route, to endure a life of brutality on colonial plantations. Cugoano wrote:

“Being in this dreadful captivity and horrible slavery, without any hope of deliverance, for about eight or nine months, beholding the most dreadful scenes of misery and cruelty, and seeing my miserable companions often cruelly lashed, and as it were cut to pieces, for the most trifling faults; this made me often tremble and weep, but I escaped better than many of them.”[ii]

On this transatlantic journey, from Grenada to England, as an enslaved servant, Cugoano would not have been confined to the hold, but the horrors of what he had endured previously must have been very fresh in his mind. The ship landed at Portsmouth on 15th July 1772 and the Homes, Campbell and Cugoano travelled to London. Prior to, during and after this voyage, Ninian was unwell with an illness that caused ‘dysentery’ and was sent by a doctor to Scotland to recover. Ninian and Penelope arrived at Wedderburn Castle, owned by Ninian’s uncle, Patrick, on 18thAugust.[iii] [iv]

At the same time, or shortly afterwards, in late 1772, Campbell came to visit Ninian and Penelope Home at Paxton House which the couple had previously rented. It would have been unthinkable for Campbell to have left Cugoano somewhere else as he was viewed as a valuable young servant, so Cugoano would have accompanied his master and stayed at Paxton. Cugaono, as Campbell’s personal servant, was likely to have been dressed in smart clothing to show off his master’s wealth and status.

Their stay coincided with the time that Ninian and Penelope were negotiating with Ninian’s uncle Patrick on the sale price of Paxton. Paxton must have had rented furniture in it at the time, as the commissions for the furniture supplied by Thomas Chippendale had not yet begun. The likeliest item that is still in place today was the dining table which was there before 1774. Can you imagine what it was like for Cugaono living at Paxton House then?

Paxton may have been the first grand country house Cugaono had entered in Britain. The interiors in 1772 were still unfinished in parts (the Drawing Room, for instance, wasn’t furnished until 1789-91), and probably contained limited amounts of rented furniture. The land around the House was still being landscaped and any trees were probably quite small.

Cugaono would have met the local Scottish servants employed by the Home family. How they treated him and what he made of them is unknown. We don’t know if Ninian and Penelope also brought enslaved servants with them to Scotland at this point in time; however, in 1788 the family archives reveal that they brought two enslaved servants from Grenada to Paxton: Tom, Ninian’s valet, and Martine, Penelope’s maidservant.

By that point, the Knight vs. Wedderburn court case had been held in Scotland (in 1778) and it found that slavery was not a condition recognised in Scotland. However, this was not widely known, and unless an enslaved person brought to Scotland was made aware of this recent ruling, they were unlikely to be able to leave their ‘owner’ for good. Adverts in the British newspapers of the time commonly described an enslaved runaway’s appearance and clothing, to get them recaptured.

In England, the Somerset case, in 1772, ruled that, ‘a master could not seize a slave in England and detain him preparatory to sending him out of the realm to be sold’. It also ruled that habeas corpus was a constitutional right available to slaves to forestall such seizure, deportation, and sale, because they were not chattel, or mere property – they were servants and thus persons invested with certain (but limited) constitutional protections.[v] Somerset winning his freedom led to around 200 Black people in London gathering to celebrate in a public house in Westminster which culminated in a Ball.

Cugaono and Campbell travelled to London after their visit to Scotland. Cugaono wrote that his master supported him in learning to read and write by sending him to a school. Cugoano obtained his freedom and left Campbell’s service. His baptism at St James’s Church, Piccadilly, must have been a truly momentous occasion for Cugoano and he came became deeply religious. (St James’s is currently commemorating this anniversary with a series of events.)

The next that is known about Cugoano’s life is that he was employed by 1784, or earlier, and until c.1791 in service of the artists, Richard and Maria Cosway. Maria strongly supported female education, and had trained under Zoffany, Batoni, and several other prominent Italian and British artists in Italy in the 1770s. She exhibited at the Royal Academy. Richard, her husband, was a celebrated miniature painter. The Cosways lived at 81 Pall Mall, London, part of Schomberg House. Their social circle included many artists, musicians, writers, politicians, and royalty, in the form of the Prince of Wales. Cugoano was therefore in the midst of this extraordinary household and evidently was able to converse with many of the people he met. Cugoano was portrayed in 1784 by famous artist, Thomas Rowlandson, in a triple portrait engraving of Cugoano with Richard and Maria Cosway (this engraving was formerly attributed to Richard Cosway).

The next that is known about Cugoano’s life is that he was employed by 1784, or earlier, and until c.1791 in service of the artists, Richard and Maria Cosway. Maria strongly supported female education, and had trained under Zoffany, Batoni, and several other prominent Italian and British artists in Italy in the 1770s. She exhibited at the Royal Academy. Richard, her husband, was a celebrated miniature painter. The Cosways lived at 81 Pall Mall, London, part of Schomberg House. Their social circle included many artists, musicians, writers, politicians, and royalty, in the form of the Prince of Wales. Cugoano was therefore in the midst of this extraordinary household and evidently was able to converse with many of the people he met. Cugoano was portrayed in 1784 by famous artist, Thomas Rowlandson, in a triple portrait engraving of Cugoano with Richard and Maria Cosway (this engraving was formerly attributed to Richard Cosway).

Cugoano is not subservient in this portrait, contrary to many depictions of Black people in other European works of art. An early biographer of Cosway recounted that Cugoano was attired “in crimson silk with elaborate lace and gold buttons, and, later on, in crimson Genoa velvet, in imitation of the footmen at the Vatican.”

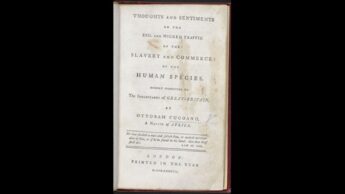

In 1787, the year before Tom and Martine came to Paxton with Ninian and Penelope Home, Cugaono published his seminal book, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, humbly submitted to the inhabitants of Great-Britain, by Ottobah Cugoano, a native of Africa. His publication was sent to King George III and other influential British figures, such as the politician, Edmund Burke. Cugoano was supported by some of the artists in the Cosways’ circle, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy, James Northcote, Joseph Nollekens, and Richard Cosway, who subscribed to the second edition of Cugoano’s book.

In 1787, the year before Tom and Martine came to Paxton with Ninian and Penelope Home, Cugaono published his seminal book, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, humbly submitted to the inhabitants of Great-Britain, by Ottobah Cugoano, a native of Africa. His publication was sent to King George III and other influential British figures, such as the politician, Edmund Burke. Cugoano was supported by some of the artists in the Cosways’ circle, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy, James Northcote, Joseph Nollekens, and Richard Cosway, who subscribed to the second edition of Cugoano’s book.

In this book, Cugaono described his early life and status, and his capture in the forest near his home in the Fante village of Agimaque or Ajumako in what is now modern-day Ghana.

“I was born in the city of Agimaque, on the coast of Fantyn; my father was a companion to the chief in that part of the country of Fantee, and when the old king died I was left in his house with his family; soon after I was sent for by his nephew, Ambro Accasa, who succeeded the old king in the chiefdom of that part of Fantee known by the name of Agimaque and Assinee. I lived with his children, enjoying peace and tranquillity, about twenty moons, which, according to their way of reckoning time, is two years.

I was sent for to visit an uncle, who lived at a considerable distance from Agimaque. The first day after we set out we arrived at Assinee, and the third day at my uncle’s habitation, where I lived about three months, and was then thinking of returning to my father and young companion at Agimaque; but by this time I had got well acquainted with some of the children of my uncle’s hundreds of relations, and we were some days too ventursome in going into the woods to gather fruit and catch birds, and such amusements as pleased us. One day I refused to go with the rest, being rather apprehensive that something might happen to us; till one of my play-fellows said to me, because you belong to the great men, you are afraid to venture your carcase, or else of the bounsam, which is the devil. This enraged me so much, that I set a resolution to join the rest, and we went into the woods as usual; but we had not been above two hours before our troubles began, when several great ruffians came upon us suddenly, and said we had committed a fault against their lord, and we must go and answer for it ourselves before him.

Some of us attempted in vain to run away, but pistols and cutlasses were soon introduced, threatening, that if we offered to stir we should all lie dead on the spot. One of them pretended to be more friendly than the rest, and said, that he would speak to their lord to get us clear, and desired that we should follow him; we were then immediately divided into different parties, and drove after him….”

After around two weeks of travel and trickery, they came…

“…to a town, where I saw several white people, which made me afraid that they would eat me, according to our notion as children in the inland parts of the country. This made me rest very uneasy all the night, and next morning I had some victuals brought, desiring me to eat and make haste, as my guide and kid-napper told me that he had to go to the castle with some company that were going there, as he had told me before, to get some goods. After I was ordered out, the horrors I soon saw and felt, cannot be well described; I saw many of my miserable countrymen chained two and two, some hand-cuffed, and some with their hands tied behind. We were conducted along by a guard, and when we arrived at the castle, I asked my guide what I was brought there for, he told me to learn the ways of the browfow, that is the white faced people. I saw him take a gun, a piece of cloth, and some lead for me, and then he told me that he must now leave me there, and went off. This made me cry bitterly, but I was soon conducted to a prison, for three days, where I heard the groans and cries of many, and saw some of my fellow-captives. But when a vessel arrived to conduct us away to the ship, it was a most horrible scene; there was nothing to be heard but rattling of chains, smacking of whips, and the groans and cries of our fellowmen. Some would not stir from the ground, when they were lashed and beat in the most horrible manner…

From the time that I was kid-napped and conducted to a factory, and from thence in the brutish, base, but fashionable way of traffic, consigned to Grenada, the grievous thoughts which I then felt, still pant in my heart; though my fears and tears have long since subsided. And yet it is still grievous to think that thousands more have suffered in similar and greater distress, under the hands of barbarous robbers, and merciless taskmasters; and that many even now are suffering in all the extreme bitterness of grief and woe, that no language can describe. The cries of some, and the sight of their misery, may be seen and heard afar; but the deep sounding groans of thousands, and the great sadness of their misery and woe, under the heavy load of oppressions and calamities inflicted upon them, are such as can only be distinctly known to the ears of Jehovah Sabaoth.”

In 1787, when Cugoano published his seminal book, he wrote, describing the West-India slaves;

“For the slaves, like animals, are bought and sold, and dealt with as their capricious owners may think fit, even in torturing and tearing them to pieces, and wearing them out with hard labour, hunger and oppression; and should the death of a slave ensue by some other more violent way than that which is commonly the death of thousands, and tens of thousands in the end, the haughty tyrant, in that case, has only to pay a small fine for the murder and death of his slave.”

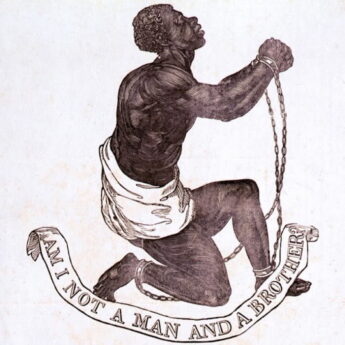

Cugoano argued for enslaved people to be given their liberty and freedom. He pointed out the false narratives used by those prolonging enslavement:

“Some pretend that the Africans, in general, are a set of poor, ignorant, dispersed, unsociable people; and that they think it no crime to sell one another, and even their own wives and children; therefore they bring them away to a situation where many of them may arrive to a better state than ever they could obtain in their own native country.”

Cugoano’s publication was the first book written by an African to demand the total abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire. His powerful account of his first-hand experiences and Christian rhetoric against slavery lent great weight to the abolition movement.

In the 1780s, around 20,000 people in Britian were Black, out of an overall population of 5 million. Many lived in London and during this decade several Black writers and activists got together and called themselves the ‘Sons of Africa’. Cugaono was an important member of this campaigning group whose other members were; Gustavus Vassa, George Robert Mandeville, William Stevens, Joseph Almaze, Broughwar Jogensmel [Jasper Goree], James Bailey, Thomas Oxford, John Adams, George Wallace, Yahne Aelane [Joseph Stuart], Cojoh Ammere [George Williams], Thomas Cooper, William Greek, and Bernard Elliot Griffiths. The Sons of Africa sought to make known the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade and to abolish the institution of slavery in the British colonies. They were deeply involved in the anti-slavery movement and worked intimately with the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, a non-denominational group founded in 1787 by Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson.[vi]

In 1786, Cugoano managed, with the help of William Green and Granville Sharp, to prevent Henry Demane, an African who had been kidnapped by slave-traders, from being shipped from Britian to the West Indies. In 1790, Cugoano, must have been aware that his former enslaver, Alexander Campbell, was representing West India planters in giving evidence to support the continuation of the transatlantic slave trade in Parliament. Cugoano disappears from the historical records after 1791, but his presence at Paxton and his efforts to end slavery have certainly not been forgotten.

Notes:

[i] Campbell was a Scot, from Islay, who became a merchant and enslaver in the Caribbean. Shortly after the Treatise of Paris, in 1763, (when Grenada became a British colony) Campbell borrowed £40,000 from his relations to purchase two plantations in Grenada with nearly 300 enslaved people. He later owned up to fourteen plantations and acted as a spokesman for West Indian planters in London. He was captured and killed in the Fedon Uprising in Grenada, along with Ninian Home, in 1795.

[ii] Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species,(London, 1787).

[iii] National Records of Scotland (NRS), GD267/22/7 Letter from George Home to Patrick Home (Naples), 27 July 1772

[iv] NRS, GD267/22/7, Letter George Home to Patrick Home (Rome) 27 August 1772

[v] https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/kenwood/history-stories-kenwood/somerset-case/

[vi] https://equianosworld.org/associates-abolition.php?id=2