Clothes for the Caribbean

Rebecca Olds, postgraduate student at the University of Glasgow, shares her discoveries about the wardrobe owned by Ninian Home in 1795 using evidence from the Home Family archives.

In 1795, Ninian Home, the owner of Paxton House, met with a violent death in one of Britain’s colonies in the Caribbean, Grenada, where he had been serving as Lieutenant-Governor since late 1792. Ninian, along with about 50 other British plantation owners, sailors, and others, was captured in Fédon’s Uprising against British rule in Grenada. He was executed by the freedom fighters on 8 April 1795 and, during the course of the uprising, his plantation, Waltham, was sacked. See Caribbean Connections.

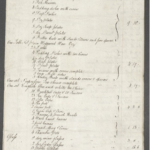

Shortly after Ninian’s death in Grenada, an inventory was taken of his possessions there. This document survives in the Home Robertson family records at the National Records of Scotland, offering a rare glimpse into the life of a Scot living in the Caribbean in the closing years of the eighteenth century. The inventory lists the contents of two trunks containing “Wearing apparel”. Each garment is identified by name. With a few exceptions, these are all garments that men back in Britain would have recognised in their own wardrobes. This article will highlight how Ninian conformed to social norms in his attire, while also using fabric choices to adapt items in his wardrobe to better suit his lifestyle as a planter in the warm, humid climate of the Caribbean.

Three piece suits

The backbone of a man’s wardrobe in the 18th century was the three-piece suit of the time, consisting of a coat, waistcoat, and breeches. By the 1790s, having a suit with all three pieces made from the same matching fabric was no longer fashionable, and Ninian’s wardrobe reflects the flexibility of a more mix-and-match approach rather than fixed ensembles. He owned 7 coats, 27 waistcoats and 24 pairs of breeches in Grenada. In a business or social setting, he may have presented himself in an ensemble similar to this one:

Woollen fabrics made up the backbone of a British gentleman’s wardrobe in the 18th century and Ninian’s inventory includes outer garments like waistcoats and breeches that were made of “flannel” and “cloth”, both of which were types of wool. But Ninian also had breeches made of corduroy, which was, back then just as now, a hardwearing yet comfortable fabric. Back in Scotland, Ninian might have chosen leather breeches, especially for riding on horseback. But in Grenada, corduroy was a cooler, more breathable option, perfect when outdoors overseeing construction projects on the plantation and directing enslaved workers in the fields.

Underneath his suits of clothes, Ninian wore the underwear of the day: shirts and drawers made of linen or cotton. For much of the eighteenth century, shirts alone served as the main item of body linen for British men, protecting the skin from outer clothing, and likewise clothing from the sweat and oils of the body. By the end of the century, drawers began to feature a bit more in clothing inventories, especially in warm climates where drawers served as a washable barrier, a kind of changeable lining to the breeches being worn. Body linens like shirts and drawers were laundered after every wear, while outerwear was not. The domestic servants in Ninian’s house, whether free or enslaved, knew how to keep his coats, waistcoats and breeches fresh and presentable by airing them out, brushing off any loose dirt and treating stains with an appropriate spot cleaner. Meanwhile, after a hot day of doing paperwork or walking the fields, Ninian could simply change his underwear – from a supply of 40 shirts and 10 pairs of drawers – to feel fresh as a daisy again!

As the case with other men of his station back in Britain, Ninian had many pairs of stockings. The inventory lists at least 89 pairs! Of these, 15 were cotton, 10 were ‘thread’ (made from yarns spun from flax, the same plant fibre that produced linen fabric), possibly as many as 38 were silk and another 35 were worsted (from yarns finely spun from sheep’s wool). Stockings in the 18th century were long enough to come up to a man’s knees and tuck in under the knee bands of his breeches. Most stockings in the 18th century were knitted with a frame knitting machine and most if not all of Ninian’s were probably sourced from Britain, particularly as Scotland had a thriving industry in producing knitted stockings.

Adapting to the Caribbean

Looking at the textiles or fabrics that Ninian’s garments were made of gives us more insight into life on the Caribbean plantations. The inventory did include garments made of the same fabrics as were in his wardrobe at Paxton House in Scotland, but also included garments of textiles especially well-suited to the Caribbean climate, which his contemporaries back in Scotland were not wearing, or at least, not so often.

Wools and silks would have featured heavily in Ninian’s wardrobe at Paxton House, but these fabrics were much too hot for everyday wear in the Caribbean. The inventory reveals that, as well as “flannel” and “cloth” breeches mentioned above, Ninian owned, at the time of his death, five pairs of breeches made of “nankeen”. Nankeen was a cotton grown in China that was naturally a golden colour. It became so popular that cotton merchants and manufacturers in Manchester began dyeing white cotton grown in Britain’s colonies a similar shade of yellow and marketing it as “nankeen” as cheap competition against the ‘real thing’ from China.

Whether Chinese or American, nankeen cotton was ideal for making tough, lightweight, comfortable breeches worn in the Caribbean and the southern American colonies, such as the pair pictured left.

As well as clothing, the inventory lists large quantities of fabric that Ninian considered necessary for caring for the needs of everyone he took responsibility for, including servants and enslaved people. Many of the textiles he owned were suitable for multiple uses, from clothing to household linens and furnishings. Ninian owned nearly 100 yards of cotton “diaper” and 45 yards of “fine striped Dimity”. Both diaper and dimity were types of fabrics made of cotton or linen that had patterns woven into them. Scotland produced several types of diaper in the 18th century. Ninian imported goods directly from Scotland in a variety of ways: via ships in which he owned shares, by placing orders through captains of other ships that delivered supplies from Scotland, and by ordering goods from London merchants who in turn sourced fabrics from Scotland.

Diaper featured small, even repeating patterns of geometric shapes such as diamonds, rectangles or square. Its use is well-documented for summer clothing, especially waistcoats and breeches.

Dimity was a lightweight fabric made of cotton, linen or a mixture of the two, with raised stripes or cords running lengthwise through the cloth. The weave produced a striped effect that could be both seen and felt. An example of breeches made from a cotton/linen mix dimity, used as summer wear, is pictured left.

Ninian had a variety of clothing items made from calico and cambric. The name “calico” (sometimes spelled with an ‘e’ at the end) came from the city of Calcutta and was used as an umbrella term for a huge range of cottons of every quality that were produced in India. One trunk contained 34 shirts made of calico and another had three pieces of calico designated as wrappers. The shirts were no doubt of considerably finer calico than the calico used for wrapping goods or cargo. Cambric was even finer than calico shirt material, but it was linen, not cotton. In France, cambric was called batiste, a textile term that is still in use today for a very fine cotton rather than linen.

While it is fascinating to see what Ninian had in his wardrobe in Grenada as a way of understanding his life there, it is also interesting to notice that, for whatever reason, the inventory did not include hats or trousers.

Trousers certainly existed in the period but back in Britain they tended to be worn as a kind of cover-all, worn over breeches when working. They were understood as being workwear and not fashionable but this was beginning to change in the 1790s. Gentlemen turned to wearing trousers when out in the Caribbean more readily than they did in Britain and the rest of Europe, as a cooler alternative to breeches. The illustration below depicts a French plantation owner wearing trousers on his Caribbean plantation.

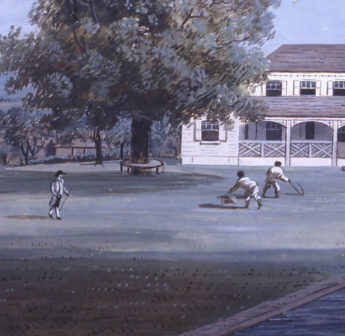

As for hats, we do not know why no mention of them is made in the inventory, but it is almost inconceivable that Ninian might not have owned any. The painting of Ninian on his Paraclete plantation in Grenada, below, certainly shows him wearing a large-brimmed hat. From this painting, we can also see that Ninian dressed according to his status and identity as a British businessman and gentleman, while the inventory tells us that he adapted his wardrobe as needed for ease and comfort in the hot, humid Caribbean climate.

Header image: Adam Callander (1750-1817), A View of the Paraclete Estate House, Grenada [detail], 1789, gouache on paper, The Paxton House Trust

Header image: Adam Callander (1750-1817), A View of the Paraclete Estate House, Grenada [detail], 1789, gouache on paper, The Paxton House Trust

Download the original inventory here, a transcript here. Other archival records relating to slavery can be accessed here.

Rebecca Olds is a postgraduate student enrolled on the MLitt Dress and Textile Histories course at the University of Glasgow. She is currently writing her dissertation exploring why elite women in the Scottish Highlands desired to have gowns made of fashionable London silks in the early 18th century. Rebecca hopes to continue her research through PhD studies, focusing on women’s participation in the garment-making trades in the Scottish Highlands during the 18th century. She was involved in Paxton House’s Georgian Dressmaking Live! event in Spring 2023. The sackback gown she helped to make as part of that event in currently on display in the dining room. To see it, book a house tour here.

Rebecca Olds is a postgraduate student enrolled on the MLitt Dress and Textile Histories course at the University of Glasgow. She is currently writing her dissertation exploring why elite women in the Scottish Highlands desired to have gowns made of fashionable London silks in the early 18th century. Rebecca hopes to continue her research through PhD studies, focusing on women’s participation in the garment-making trades in the Scottish Highlands during the 18th century. She was involved in Paxton House’s Georgian Dressmaking Live! event in Spring 2023. The sackback gown she helped to make as part of that event in currently on display in the dining room. To see it, book a house tour here.