Paxton and Slavery in the Caribbean

A Description of the Island of Grenada and its Different Quarters, of 1760, described the island as; ‘full of large mountains forming several fertile valleys and producing a great number of fine rivulets, which facilitate the construction of water mills for the use of sugar plantations.’

Caribbean Connections and slavery

Ninian Home (1732-1795) was a nephew of Patrick Home, who built Paxton House. As a junior member of the family, Ninian had to earn his living. First, in 1749, he was sent from Scotland to his uncle George Home (1698-1760), who had been transported to Virginia following imprisonment after the 1715 Jacobite Uprising. George lived in Culpeper County, Virginia, and Ninian was to ‘keep his master’s store’. George, as a land surveyor, knew many plantation and slave owners, including George Washington.

Ninian spent much of his career in the Caribbean, though he returned to Scotland several times. Ninian worked on St Kitts (1756-59 and was still listed as being ‘of St Kitts’ in 1765), and became involved in shipping cargo around the Caribbean, including enslaved people. He had joint shares in several ships.

Ninian went to Grenada immediately after this French colony was ceded to Britain under the Treaty of Paris of 1763. He married Penelope Payne, probably a British planter’s daughter, between 1764 and 1768. They had no children, and she died in Grenada on 30th September 1794.

Grenadian Plantations

In 1764, Ninian bought the 400-acre plantation of Waltham on the north-west coast of Grenada with a huge mortgage of £17,000 – very little of which he actually paid back in his lifetime. The terms of the mortgage compelled him to sell all produce through an agent who deducted charges, interest, and repayment instalments, leaving any profit balance for Ninian. (This mortgage was not cleared until 1836 by his heirs). He also bought a third share of Paraclete plantation (100 acres), near the east coast of Grenada in St Andrews Parish, with his cousin and uncle Patrick Home acquiring another third of this (for £4,747 9s 5d). Patrick sold his share in 1770. Ninian appears to have sold his share in Paraclete to his friend Alexander Campbell by the mid-1780s, having previously considered its sale to fund his purchase of Paxton House in 1773. Ninian purchased Paxton from Patrick Home for £12,000 via a loan of £10,000 secured upon the estate and by using funds from the sale of his inherited farm of Jardinefield, Berwickshire.

By 1789, Ninian had over 200 enslaved people on Waltham, the oldest of whom was 90-year-old Agatha and the youngest, named Bristol, was only two months old; children were born into slavery and like their parents, were the property of their master. At the peak of his business, Ninian ‘owned’ around 200 enslaved people at Waltham, and a further 56 at his ‘small share’ of Alexander Campbell’s plantation on Mustique. The archives detail their first names, ages, occupations and, sometimes, additional information such as any illnesses or abilities. The archives can be searched online.

Crops grown on the plantations were primarily sugar and cotton, along with some cocoa, and coffee. Although Ninian’s income fluctuated due to diseases affecting the enslaved people, storms damaging crops (1781, 1786, and 1787 crops were wiped out by hurricanes), market forces, and produce being lost in shipwrecks whilst being transported to market, he was still able to make profits. Ninian applied his profits to furnishing Paxton House and improving and extending his estates.

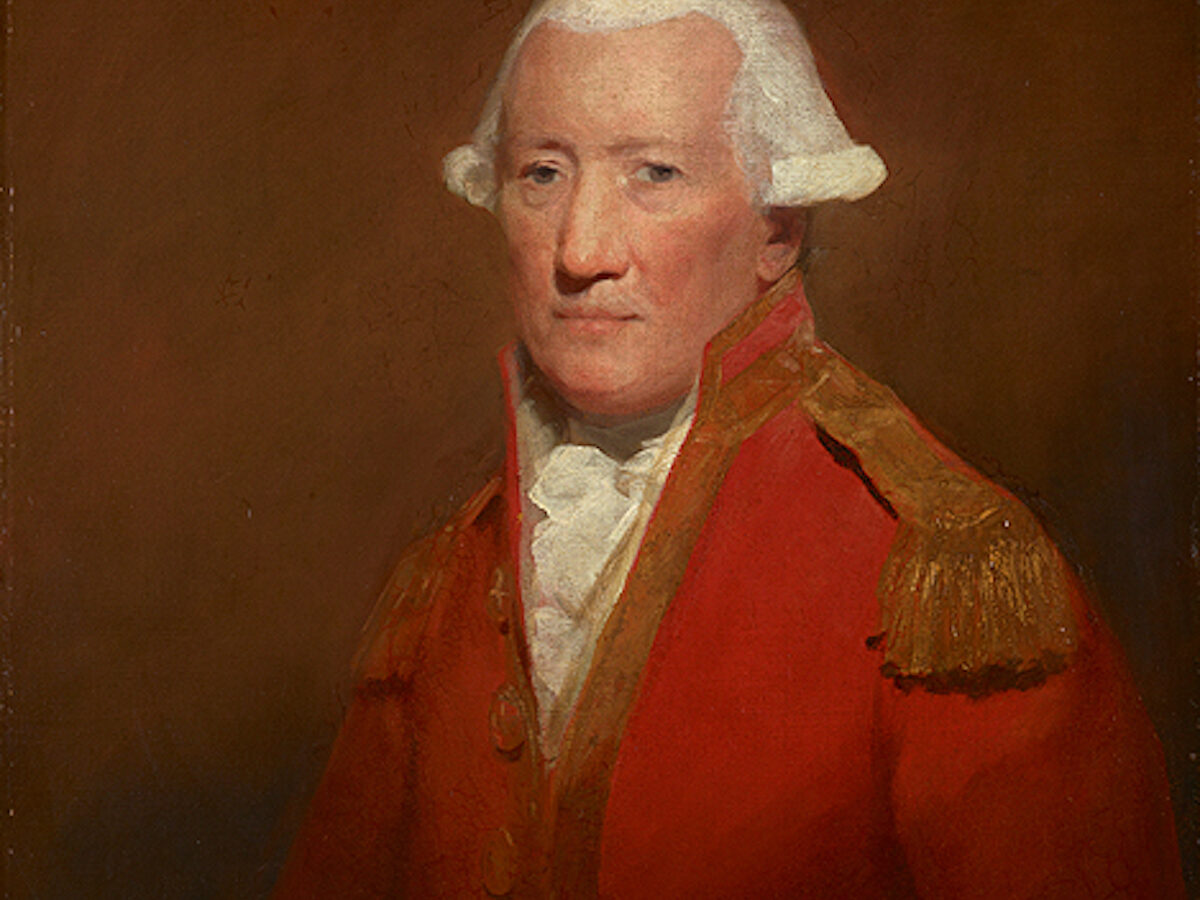

During Ninian’s residence in Grenada, he craved a remunerated government office which would yield both prestige and a secure source of income. Eventually, after much campaigning on his behalf by both Patrick and George Home, Ninian was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Grenada in late 1792.

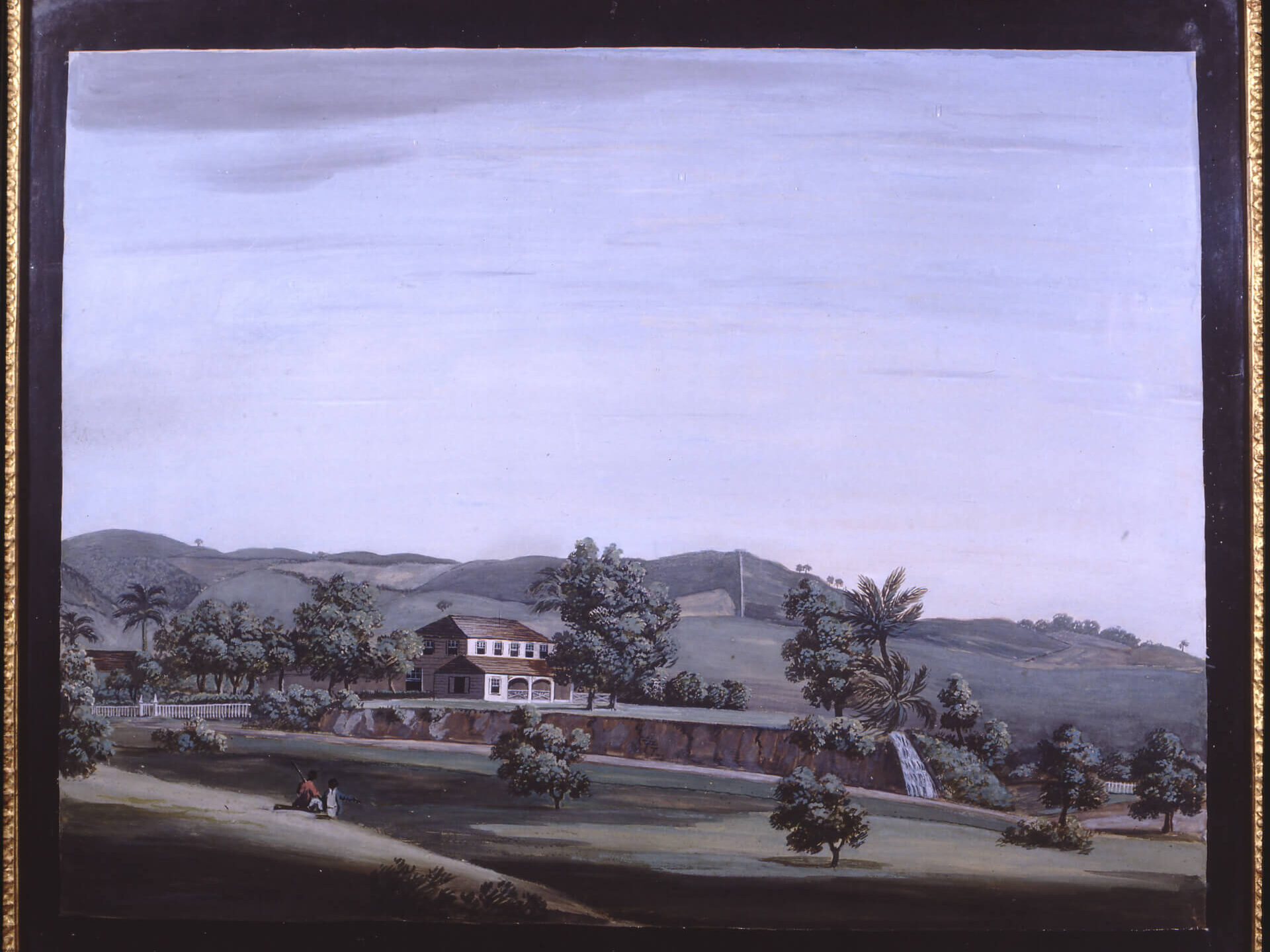

Detail of Adam Callander’s 1789 painting showing enslaved people maintaining the grounds of Ninian’s Paraclete estate, with a white man, possibly Ninian, in the foreground. The stepped waterfall was not just a picturesque landscape feature created by the hard work of enslaved people; it was used to transport the cut sugar cane to the sugar processing factory.

Treatment of enslaved people by Ninian Home

Archive documents suggest that Ninian was concerned about the welfare of enslaved people on his plantations. He provided a Scottish-trained doctor to treat their illnesses or injuries; enslaved pregnant women were allowed to stop work for a short period prior to the birth of their baby and nursing mothers were allowed up to a year off. Surviving letters show that enslaved people were allocated gardens to cultivate food for themselves and were allowed to sell any excess at market. This food production meant slave owners (enslavers) were less reliant upon imports (such as oats and salted herring from Scotland).

In general, plantation managers and overseers treated enslaved people notoriously harshly. One overseer at Waltham, Ninian Jaffray, appointed when Dr. William Bell was the manager for Ninian there, turned out to be abusive and cruel. Ninian wrote to him:

Ninian may have been influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment ‘sense of humanity’, but no doubt he was also influenced by the idea that enslaved people who were healthier and more cooperative would improve his profits.

Ninian was heavily invested in the slavery system and campaigned against the abolition of the slave trade. He wrote repeatedly to his uncle Patrick Home, then MP for Berwickshire, to vote against abolition.

Death of Ninian in the uprising of 1795 on Grenada

Grenada had been a French colony until 1763 and French control was temporarily restored from 5 July 1779-3 Sept 1783. Under British colonial rule, several estates remained in French ownership. Ongoing conflict between Britain and France caused friction between French (Roman Catholic) planters; their British (Protestant) neighbours; and the British colonial authorities. White French proprietors, freed people of colour, and many enslaved people were hostile to the British.

In 1789, ‘The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen’ in France led to French citizenship being granted to freed people and emancipation of enslaved people in French Caribbean territories. The news of this spread and inspired unrest for those seeking freedom. In March 1795, Julien Fédon led an uprising on Grenada against the British authorities and British planters. Fédon was the son of a Frenchman and a freed black woman and owned the 360-acre Belvedere estate and 96 enslaved people.

The uprising lasted around a year and caused devastation to the island and its economy. Around 7000 enslaved people were killed in fighting, or in retaliation for their insurrection, and many others were deported. Ninian Home was captured by the rebels in early March 1795 and held for a month in a well-defended camp on Mount Qua-Qua, above Belvedere estate. After Fédon’s brother was killed by the British, Fédon ordered the killing of 48 of the 51 captives (Governor Ninian Home, Alexander Campbell, and other white planters and British sailors). They were shot and their bodies mutilated; Ninian was the last to be killed on 8th April 1795. A Scottish doctor, Dr John Hay, a minister, and one other man were spared.

Detail of Adam Callander’s 1789 painting of Paraclete showing enslaved people working in the gardens and their homes in the middle distance. Ninian may be seated under the tree. The water feature was used to transport the cut sugar cane down to the factory. The unbleached cloth for the enslaved people’s clothing was probably made in Scotland. The Callander paintings do not show the harsh realities of life on the estates.

Grenadian plantations from 1796

After Ninian’s death Waltham plantation passed to George Home (1735-1820), Ninian’s younger brother, who never visited Grenada. From c.1796/7, George Home sent his own money, and borrowed a further £13,000 to repair and reinstate parts of the plantation that were damaged during the uprising. George was an Edinburgh-based lawyer and from 1781-1806 was one of the principal clerks to the Court of Session. George retained ownership of the estates as an absentee landlord using agents to manage them. It appears that the plantation, and Ninian’s huge debts, were a substantial drain on George’s Scottish-based income. However, he felt obliged to retain them, believing that he had an obligation to do so for the sake of his family, employees, and dependents. He also hoped that they might eventually turn profitable, despite the Act to Abolish the Slave Trade, which was passed in Britain on 25 March 1807. This Act did not prevent the continuation of slavery in British colonies.

George died in 1820. After his death, Paxton in Scotland and Waltham in Grenada were inherited by William Foreman Home, whose brother John, had qualified as a doctor in Scotland in 1800/01. John went to work in Grenada in 1801 as the indentured estate doctor at Waltham for £100/year for three years. Aside from treating any illnesses and injuries, John also inoculated the enslaved people against smallpox and cared for the ‘old and infirm’.

George Home frequently wrote to John Foreman Home asking how the enslaved people were. For instance, George stated that the pregnant; ‘ladies… should have every reasonable comfort their situation admits of…’ (13 Sept 1801). That same month, George was pleased to hear of improved sugar crops at Waltham obtained without injury to the enslaved, adding; ‘I should feel regret if it had occasioned the negroes to be overworked, which I hope they never will be.’ What was classed as ‘overworked’ is a matter of debate.

John Foreman subsequently broke the terms of his indenture and left Waltham after little more than a year there. He went on to purchase his own plantations in Grenada.

The ‘proper’ care of the old and infirm and indeed all the enslaved people also featured in the letters from George to his estate manager, John Fairbairn, at Waltham (in post from February 1798 until c.1819). George’s concerns were, mainly, driven by commercial considerations, but he also showed a deep and lasting consideration of those in Grenada.

An overseer at Waltham, Adam Black from Duns, Scotland, was sent home in 1815, as John Fairbairn would not allow him to ‘flog or ill use’ slaves. Black had five children by enslaved women, all of whom were left behind on the estate when he left.

In 1815, the debts on the Waltham estate stood at £24,183, comprising the mortgage, interest arrears and debts to Simond and Hankey, the mortgage lenders. This was a reduction of around £3000 on the previous year, so the estate was in profit. In light of the estate’s return to profitability at this time, George Home was permitted to draw in an income (£100) for Waltham for the first time since he succeeded to the estate. In 1816, William Wilberforce was proposing legislation to prevent British planters from purchasing further enslaved people from nations still engaged in the transport of slaves (the Spaniards, Portuguese, Americans, or others). George Home’s correspondence reveals him to have been strongly opposed to the abolition of slavery in the West Indies. He believed that any regulation of slavery should come only from local assemblies in the West Indies rather than the British Parliament.

The naval career of another Paxton personality, Admiral David Milne, spanned the final years of the slave trade and the start of abolition. As a young sailor in the 1790s he fought for British control of the Caribbean while the Royal Navy was still protecting slave traders. In 1816 he had a prominent role in the Battle of Algiers, which stopped the enslavement of Europeans by the Barbary corsairs. Finally, as the Royal Navy’s commander of the North American station after the abolition of the slave trade, he organised the interception of slave ships and the return of their victims to Africa. Milne described some of the horrific conditions he and his colleagues found on the ships transporting African people to the Caribbean; but tempered his horror with the thoughts of the monetary reward the sailors would receive for the capture of the illegal ships and their cargo. They were not able to stop all the ships and others carried on their way, sometimes with additional provisions supplied by the Navy. Milne’s son, David, married Jean Home, heiress to Paxton, in 1832.

The Campaign for Abolition

Many enslaved people tried to fight against their situation with both small and greater acts of resistance and defiance. Some tried to run away temporarily or permanently (this was much harder to do on the islands). Uprisings were common in the Caribbean, particularly on the islands where enslaved people greatly outnumbered whites, but where treatment was harsher and more brutal. The ruling elite saw these events as acts of rebellion to be crushed, inflicting dreadful punishments, death and reprisals. For the enslaved and their descendants, as well as those fighting for their cause, such as the Abolitionists in Britain, these were viewed as acts of resistance to gain their freedom from bondage. Throughout the diaspora today these brave people (including Fédon) are regarded as, and celebrated as freedom fighters. Mary Prince (b.1787/8), who had been enslaved in Bermuda, Grand Turk, and Antigua, wrote in 1831: “All slaves want to be free – to be free is very sweet…The man that says slaves be quite happy in slavery—that they don’t want to be free—that man is either ignorant or a lying person. I never heard a slave say so.”

Slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1834, but in most cases the enslaved people had to work a further four years as ‘apprentices’ on British owned plantations, only then did they become free people.

In 1835, a claim from William Foreman Home, as proprietor and owner-in-fee was made to the British Government’s Slave Compensation Commission for the Waltham estate which had, at that point, 247 enslaved people, 90 of whom belonged to his brother John. William was awarded £6,226.16/- on 2 Nov 1835. In 2021, using the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, the equivalent sum awarded would be £808,906.

The process of gaining a release from the original Waltham mortgage taken out by Ninian Home in 1764 was begun in January 1835. This was undertaken in anticipation of the compensation money being awarded later that year to prevent the mortgage lender’s heirs from counterclaiming against the compensation awarded for Waltham. From the surviving documents, the sums outstanding on the mortgage were in the region of £1200-£1300. Even if this sum was subtracted from the compensation there was obviously a great deal of money left over. However, John Foreman Home wished to claim money for the 90 enslaved people which had been transferred from his estate of L’Est Terrre, Grenada, out of the Waltham compensation (which may have been around £2,268 pro rata). So, William Foreman Home may have ended up with somewhere between £2700 and £4000.

Following the abolition of slavery, sugar estates such as Waltham became increasingly unviable economic concerns. Waltham struggled to produce enough sugar to cover its costs. One of the main problems facing Waltham was retaining enough workers to undertake the cultivation and production of sugar, many other estates in Grenada were abandoned for this reason. In light of these economic realities, Waltham estate was advertised for sale in 1844. It was bought by George Walker of St Vincent for just £2,500 and the sale was completed in 1848.

Acknowledgements

This text has been compiled by Dr Fiona Salvesen Murrell and John Home Robertson with the advice of Chantel Noel and Benjamin Busenze of Descendants https://www.descendants.org.uk/. We are extremely grateful to Chantel and Benjamin for their guidance.

The sources used include original archives on loan to the National Records of Scotland, compiled by Hazel Anderson. Dr Sonia Baker shared her archival research on Ninian Home with The Paxton Trust in 2010. New information has been incorporated as a result of the work of Dr Charles Fletcher in 2021/22 with funding from The Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund delivered by the Museums Association.

Descendants is a history and arts-focused organisation aimed at children and young people aged 4-16, primarily but not exclusively of African and Caribbean descent. The main focus is on African and Caribbean culture; exploring history and experimenting with art, craft, music, drama and dance.